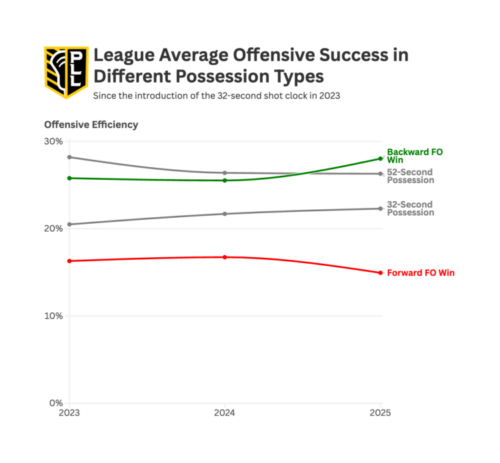

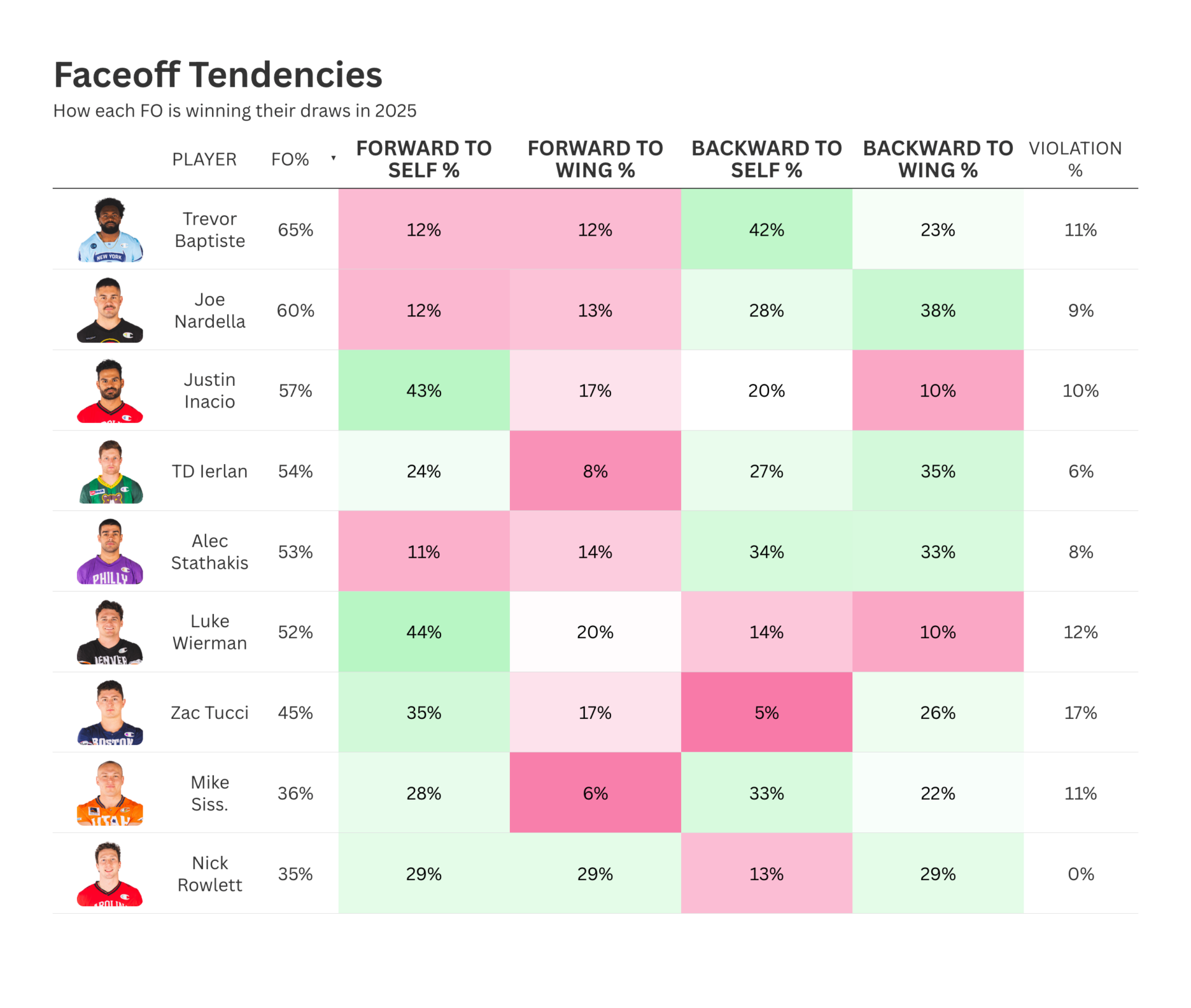

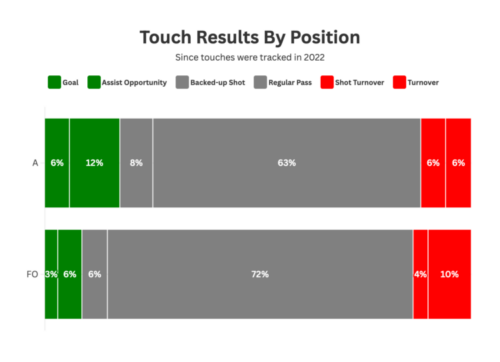

Lacrosse, at all levels, has only ever tracked faceoff performance with one stat: FO%. This does a decent job of measuring overall performance, but there is so much more that goes into every draw. Not all faceoff wins – or losses – are created equal, and they shouldn’t be measured as such. In the PLL, especially since the introduction of the 32-second shot clock after faceoffs in 2023, the way faceoff specialists convert wins into offense is more important than ever.

I went into this story trying to figure out what makes one type of faceoff win better than another, and which players do this better than others. I figured that it would all come down to time, like I concluded in my last story about clearing. A faceoff that is won quickly is more valuable than a faceoff that is won slowly — makes sense, right?

It turns out that this has little impact on offensive efficiency following the faceoff. Sure, it’s still better to win faster than slower, but fast faceoffs tend to lead to uncontrolled breaks.

But there was one variable that made a huge impact: winning backward.

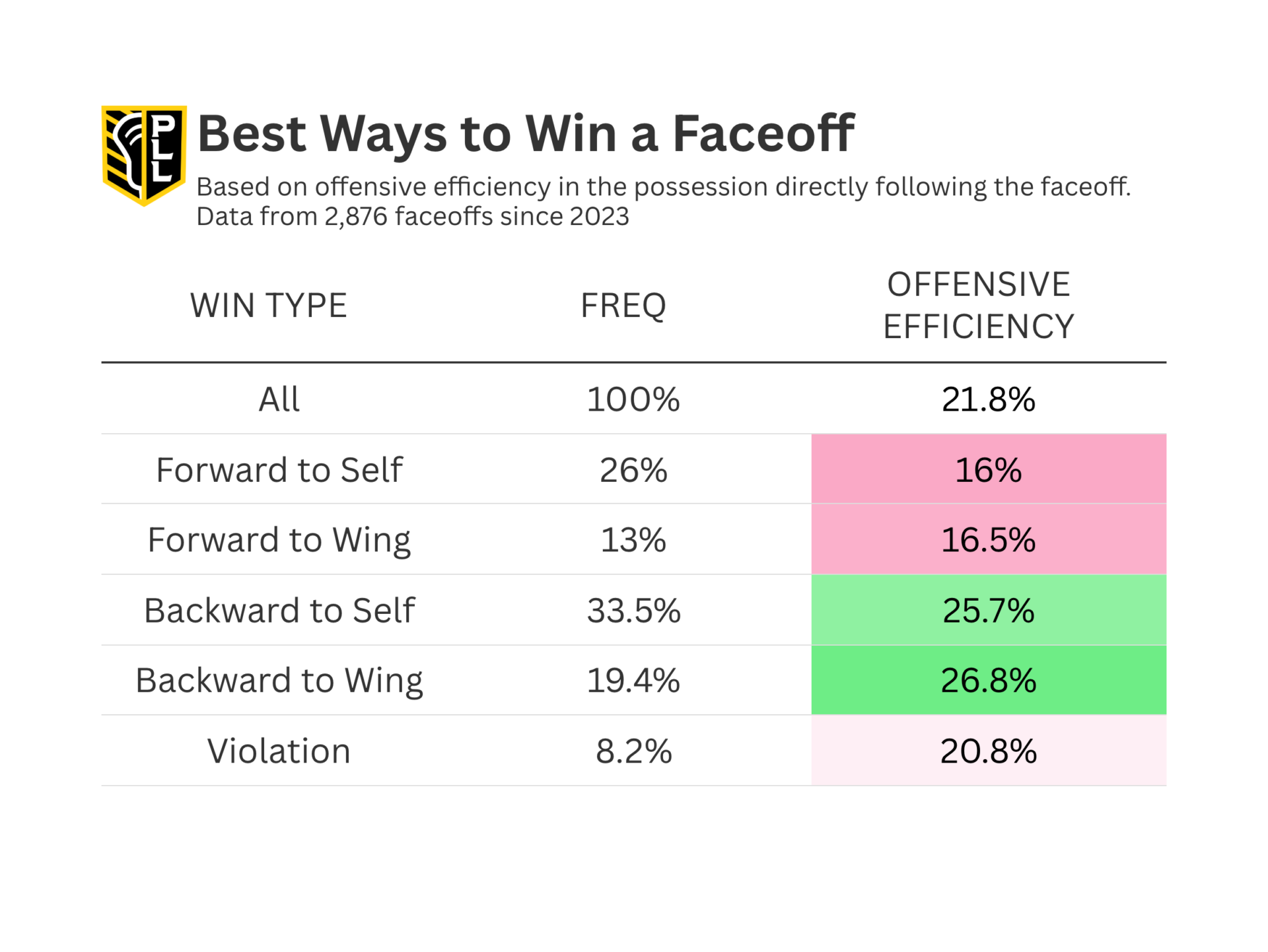

Since 2023, when the 32-second shot clock was created, there have been 2,876 faceoffs. 53% of these draws were won backward. After winning backward, teams scored on 26.1% of the ensuing possessions. After winning forward, this rate dropped to 16.2%. This isn’t just some small difference that could be attributed to confounding variables; the average PLL team is over 50% more likely to score after winning faceoffs backward compared to winning forward.