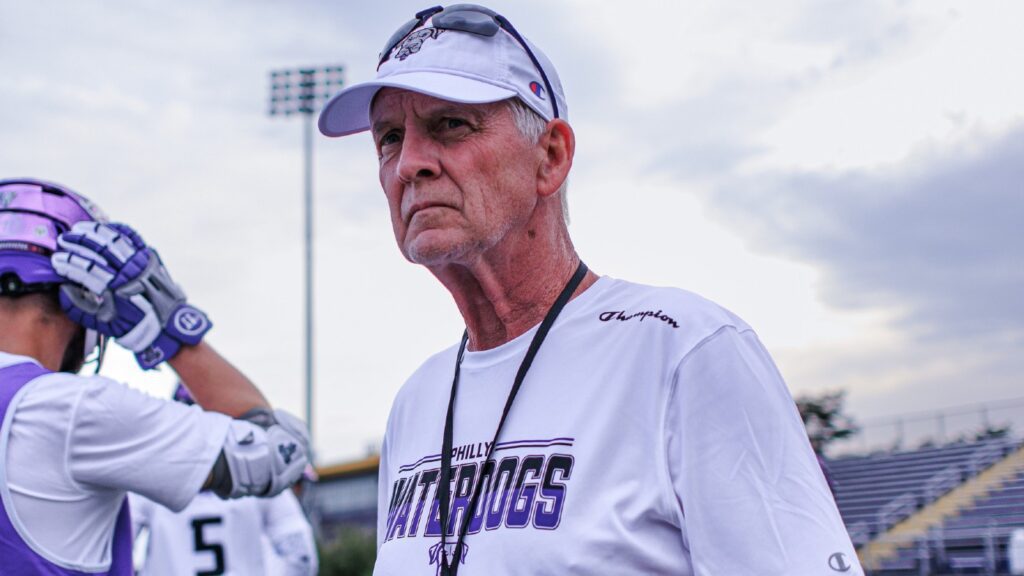

The man who dared to slide from the crease

By Wyatt Miller | May 29, 2024

Nobody slid from the crease in the early ‘90s. It was almost taboo to risk giving up that doorstep dunk.

But after two losing seasons kicked off his Division I coaching career, then-Princeton head coach Bill Tierney had to make a change. He had promised his first recruiting class in 1989 they would win a national championship at Princeton – something that hadn’t been done in 36 years. For that to happen, he couldn’t continue playing the defense employed by Johns Hopkins, the one he learned from Freddy Smith. They had to be different. They had to be unique.

“At RIT, I had been the 1983 Coach of the Year and I thought I knew my stuff,” Tierney said. “The first meeting I had with Freddy and the staff at Hopkins, I realized I knew nothing.”

Smith took Tierney under his wing, teaching him ways to influence offensive players to do things they either didn’t want to do, weren’t used to doing or weren’t allowed to do. The Blue Jays had the talent to achieve that with 1-on-1 matchups and constant communication in their “Sevens” defense. Princeton did not.

Years earlier, at RIT, Tierney implemented double-teams using early slides, but that was in Division III and it wasn’t an organized system. Before the 1990 season, he realized Princeton couldn’t win with individual matchups. They had to slide, and they had to do it from the middle if someone was there.

Tierney combined that concept from RIT with Hopkins’ vocal man defense, employing early slides to create something unheard of: the crease slide defense. This scheme didn’t just encourage slides from the crease, but actually relied upon them. Tierney knew his defenders would get beat 1-on-1. But if it was to the right spots, then it didn’t matter, because a slide was coming before a play could be made. Then, a second early slide would fill that spot, and so on. This concept defined a generation of Princeton lacrosse, leading to six national titles, and has become a staple for defenses in today’s game.

“We felt there were indicators that we were going to get beat, so let’s go (then),” said Tierney, who’s now entering his first season as a professional coach with the Philadelphia Waterdogs. “But we knew where we were going to get beat from the effort of guiding guys down the side. … It was just a culmination of some of my experiences with jumping teams and high pressure.”

As soon as the slider saw the back of the ball-carrier’s head, it was time to go. But not without communicating to the on-ball defender, or the first slider, which person would be coming over.

Similar to the “Sevens” scheme, players were constantly communicating. Every crease slide needed a perfectly timed recovery with masterful mechanics. Because of all those moving parts, they couldn’t get the slides wrong, or it would result in an easy score.

There were three pillars to this defense, according to Tierney:

- Slide to where the offensive player is going, not where he is

- Break down to avoid getting run by

- Stay in front of the ball-carrier so the on-ball defender can stay on him and get a squeeze before he rolls off to recover

“He was playing chess with the players,” defenseman Mike Mariano said. “If one of the players didn’t do what he was supposed to do, then the whole system would break down, and that’s why he was so intense.”

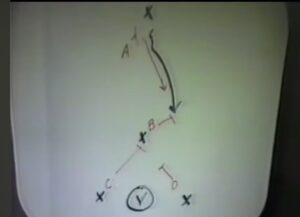

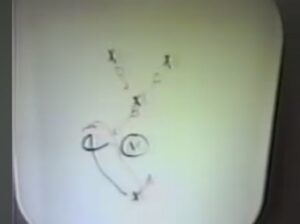

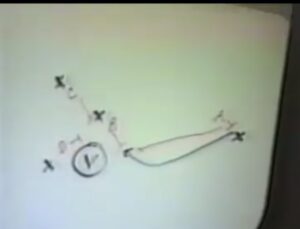

Here are three diagrams Tierney showed at a coaching convention in the ‘90s, detailing the basic tenets of his defense on an alley, X and wing dodge, respectively:

Alley Dodge:

“A” drives the top man down the side by overplaying to the middle, and “B” is the slider. “B” goes as soon as he’s confident “A” has done his job and won’t allow a rollback. When they see the stickhead of the defender go behind the lead hip, that usually means he’s beat and it’s time to go. “C” or “D” recovers based on which side the dodge comes from.

X Dodge:

“A” forces the inside roll underneath goal line extended by overplaying topside, and then “B” slides early to block the crease. “C” or “D” would then recover using the bump through technique, sliding through to cover up top, depending on direction.

Wing Dodge:

“A” drives the dodger underneath by overplaying topside and can’t let him roll back up top. “C” can then bump through and can sometimes pre-rotate to cover the crease guy. “D” can help on the crease if he has to, unless it’s a team that likes to throw to X, in which case he would shut off.

“It was all about funneling the ball-carrier to where he wanted them to be,” attackman Jesse Hubbard said. “If the slide isn’t there in time, it’s the crease guy’s fault, not the guy playing the ball.”

Another unique aspect of this defense was the idea of everyone looking at their man instead of the ball, except for the on-ball defender. That took some getting used to, but Tierney never went easy on his players.

A lot of times, he didn’t even let them use a ball in practice. They would play airball, and once the whistle blew, the man was considered beat, setting off the chain reaction. That took dropped passes and hesitations out of the equation and simplified things. Foot and hip placement were Tierney’s biggest concerns, and he could spot mistakes from the other end of the field.

“He could be coaching the offense 50 yards away,” Mariano said, “and we’d be practicing defense and he’d just stop because he saw that someone on the crease was looking at the ball and not his man, or somebody’s hips were not parallel where they should have been when the ball was two passes away from that second person who was going to do the second slide.”

Originally recruited as an offensive midfielder, Mariano ended up as an All-American defenseman under Tierney’s tutelage. He and 1993 National Player of the Year David Morrow led the unit together for three seasons, despite both having “very low expectations” for themselves, they each said.

In 1990, the Tigers’ early-season win over top-seeded Navy flipped the switch. It made the players truly believe they belonged at that level, Mariano recalled, and could win with the crease slide defense if they all bought in.

They were right. That game started a pattern of winning extremely tight games, including all but one of their overtime thrillers throughout the next three years. The energy that defense preserved thanks to a slow offense, combined with Tierney’s relentless pursuit of mastering the system, triggered Princeton’s unprecedented success.

“It was kind of indicative of that mental toughness that (Tierney) was growing in us that we were winning those close games,” Mariano said.

Once Tierney got through to Morrow, he became the linchpin. He’s been quoted saying that he “hated” Tierney when he got to Princeton and actually tried to quit the team as a freshman. But by his sophomore year, he was the top cover guy – the “A,” so to speak. He was the first true positional stopper, not a takeaway fiend like most top defensemen at the time.

Part of his success was due to the fact that Morrow was fueled by rage, so Tierney had him play differently from the rest of the team. And when things started to click for Morrow, everything fell into place around him.

“I would try to make it a mission to not get slid to,” Morrow said. “To be honest, when it came to the mechanics of team defense, I wasn’t very focused on that. … In some games, I wouldn’t even be part of the team defense. He would tell me, ‘I don’t want you sliding off that guy. You just follow that guy wherever he goes and haunt him.’”

Tierney drilled those concepts into his players’ brains with such intensity that many, Morrow and Mariano included, can still quote him 35 years later. Even the offensive players like Hubbard knew the minutiae of that defense. When he arrived in 1996, that scheme was tried and tested, having brought two national championships to the Tigers in the previous four years.

Tierney had specific game plans for every individual opponent based on their talent. He always knew where to funnel certain shooters, how quickly they could get to their spots and which hand was dominant. Tierney’s detailed nature made practice unbearable, but also made the games easier.

“Offensive teams like Syracuse, Maryland and Virginia, watching these attackmen get so frustrated with these guys in their face, it was a beautiful thing,” Hubbard said.

In the 1992 NCAA Tournament, nobody was worried about the Tigers. But then, it became clear those top teams had never seen the crease slide defense before, Mariano said, or anything like it. They were flustered, and that was just the beginning. It took nearly a decade for teams to truly figure out how to beat the crease slide consistently. By that point, Tierney had brought six national titles to Princeton in 14 years.

His creation of the crease slide defense is right up there with Buddy Ryan’s 46 defense with the Chicago Bears and Dale Brown’s “freak” basketball defense at LSU in the mid-’80s. All three were new defensive concepts in their sport that catered to their squad’s specific capabilities, leading to dramatic turnarounds for their respective teams.

“It’s like that Malcolm Gladwell book that says it takes 10,000 hours to master something,” Mariano said. “We put in the 10,000 hours to master his defense.”