When Gary Gait and Dave Pietramala went head-to-head on Norris Field for the first time in 1992, it was as teammates, in practice.

Unlike the entirety of their college rivalry that culminated in the 1989 NCAA Championship when Gait and his brother Paul led Syracuse past Pietramala and Johns Hopkins, or the 1990 World Games when Pietramala piloted Team USA to gold as the tournament MVP, the defining players of their generation wore the same jersey in the early 1990s.

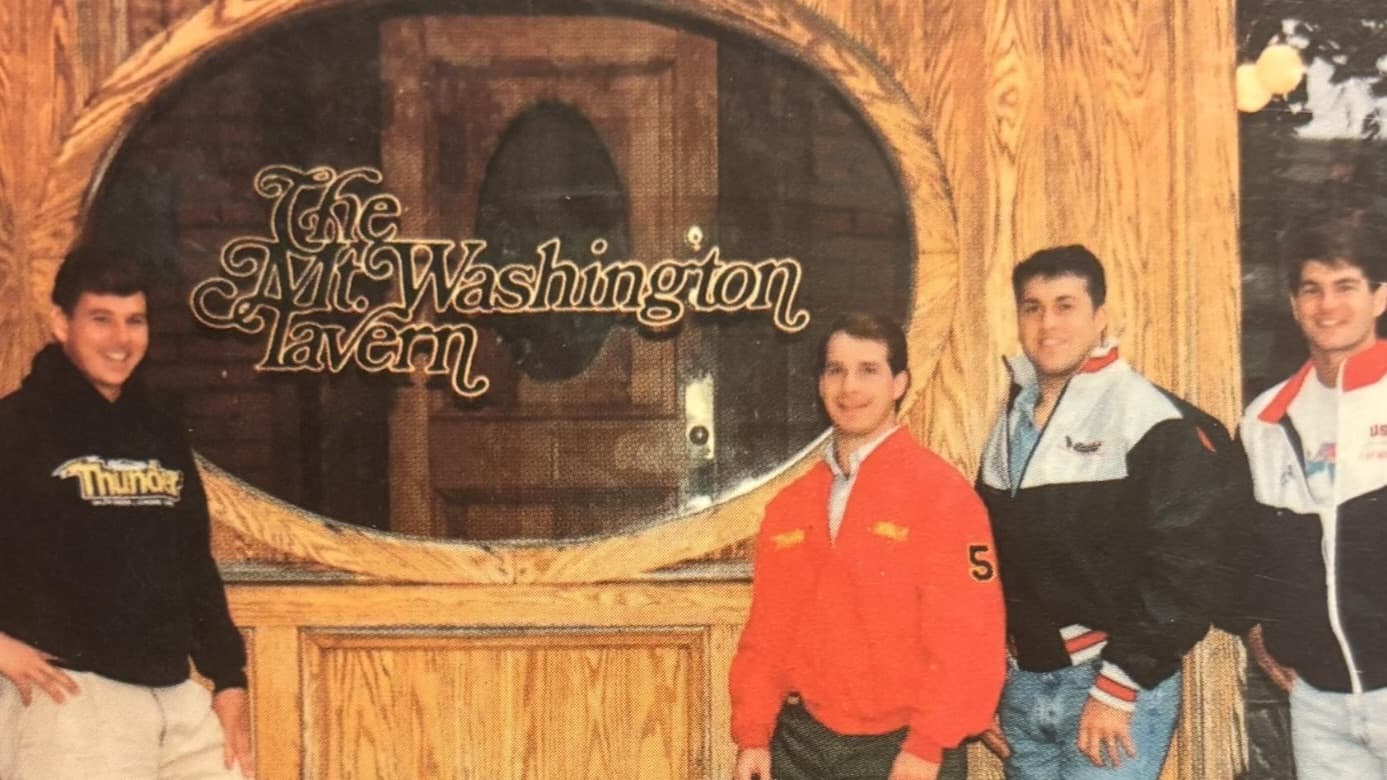

For years, the Gait brothers, Pietramala and a team of former All-Americans practiced together every Tuesday and Thursday evening as a part of the Mount Washington Lacrosse Club. Those all-time greats stayed after practice each night, dodging at each other for extended periods of time, only to pause afterward and give each other copious notes.

“That was pretty unbelievable, what we did, and the opportunity we had to work one-on-one with those guys,” Pietramala said. “When a one-on-one was done, to have a conversation about, ‘Well, this is why I did that, and what were you thinking there?’ It was almost like really talented players coaching other talented players.”

“It was a team where all these guys I played against in college and that were older and that had played all came together,” Gait said. “It was just a great way to meet all these laxers that I played against but that I didn’t know.”

While the Gait-Pietramala matchups in the NCAA and the World Games will be remembered and recounted by lacrosse fans for generations, those moments on the hidden Norris Field six miles north of downtown Baltimore are memories privy to only a select few people.

“It was quite the contest,” their Mount Washington teammate Haswell Franklin said. “I’ve seen each of them make phenomenal plays against each other.”

“It was remarkable,” head coach Skip Lichtfuss said.

The Mount Washington Lacrosse Club wasn’t any run-of-the-mill men’s league squad. The club was arguably the greatest lacrosse team of the 20th century. Bill Schmeisser – legendary Johns Hopkins head coach – helped found the team in 1904 as it sprouted from the Mount Washington Athletics Club. From that point through the 1990s, the Wolfpack dominated the lacrosse world as the preeminent destination for college lacrosse’s best after graduation.

“Coming out of college, the best players went to Mount Washington,” former Wolfpack opponent and Chesapeake Bayhawks owner Brendan Kelly said.

Mount Washington regularly beat up on the best college teams for much of the 20th century. Despite winning 35 pre-NCAA national championships, Hopkins won just 17 games in 54 matchups against the Wolfpack. Virginia’s all-time record versus Mount Washington is 1-17. Army went a more respectable 10-21. Rutgers won two games in 10 matchups. From 1925 through 1969, Mount Washington’s approximate record was 358-31, good for a ridiculous 92% winning percentage.

“The greatest players over the last century played there at one point or another,” former Wolfpack player and longtime head coach Lichtfuss said. “We beat all the best teams because we had the best players. We had a roster stacked with All-Americans all the way down the list.”

In the first World Lacrosse Championship in 1967, the Mount Washington team represented the United States in the invitational tournament after being deemed the best team in the country. They beat Australia in the final, winning the World Championship for the red, white and blue.

While more modern selection processes emerged for the national teams in the ensuing decades, seven of the 26 players on the 1994 Team USA squad were Mount Washington players, and a few more, such as the Gaits, played for Team Canada.

At one time, one of five men in the National Lacrosse Hall of Fame had either played or coached for the Wolfpack.

The Schmeisser Award – given to the best defender in college lacrosse – is named after one of Mount Washington’s founders. One of Schmeisser’s players, Francis Morris Touchstone, is the namesake for the award given to the best Division I head coach each year. Jack Turnbull, for whom college lacrosse’s Attackman of the Year award is named, also played for Mount Washington.

Four Mount Washington players have PLL awards named after them: the Gait Brothers Midfielder of the Year, the Dave Pietramala Defensive Player of the Year and the Paul Cantabene Faceoff Athlete of the Year awards.

Mount Washington even had its own field and facility. Norris Field sits off a windy back road along the Jones Falls Expressway. For 95 years, the facility, which included a clubhouse and locker room, was the home to the Wolfpack alone as they faced off against the best college and club teams in the nation on Friday nights under the lights.